Mercenaria mercenaria (not mercenaries)

Diane DiMassa, Ph.D.

So there I was, rake in hand, basket by my side, and then it happened. I didn’t see it at first because the sun was in my eyes. I never use sunglasses because they somehow always fall off when I look down. I hadn’t seen it coming, but I saw it then. There it was, not far from me at all. I looked at Kathy and she saw it too. We both smiled, taking mental notes of its path. We simply watched and waited. Soon, it would be ours. Some today. Some tomorrow. Maybe even some on Wednesday. No one else was around . . . at least for a while.

After it left, we made our way over to the site. Jackpot! We worked quickly and deliberately. It was almost too easy. It felt like we were cheating. But, as they say, timing is everything.

“Hello there!” a voice said. “License please.”

“Right here on my hat” I said. “You can read the number.” It may have felt like cheating, but we were perfectly legal – tools, time, location – all on the up-and-up.

“You measuring?”

“Yes we are. We always do.”

“Enjoy your weekend. Great day for it.”

“Oh, we will thanks. You too.”

That’s how it goes; that’s what happens; but there is so much more that goes on behind the scenes.

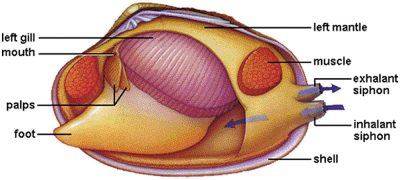

(from www.biologyjunction.com/clam_dissection.htm)

Mercenaria mercenaria, the hard clam, the northern quahog (pronounced CO-hog), aka the quahaug, is native to the eastern shores of North America. This bivalve – a mollusk that has a shell consisting of two hinged valves – has two adductor muscles that are used to control the shell, an open circulatory system, and a simple nervous system. It has no particular head, but the foot is used to dig, so that the clam can live in rather than on the sediment. Quahogs prefer salt water and survive best at a salinity of 20-25 parts per thousand. Common names for Mercenaria mercenaria, such as littlenecks or cherrystones, are dependent on size. As a rough guide, clams 1-2 inches in thickness are littlenecks, whereas clams 2-3 inches in thickness are cherrystones. Clams larger than 3 inches are referred to as chowder clams or simply quahogs. Anything smaller than 1 inch is considered a “seed clam” and should not be harvested; in fact, in most places is it illegal. Hard shell clams are filter feeders that extract nutrients from the organic matter in the surrounding water. Fortunately, all of the clam, except the shell, is edible, and people eat a lot of clams. A LOT of clams. Nature can’t keep up.

Shellfish farming on Cape Cod, Massachusetts, is big business. Grants are available for qualified individuals and regulated sites. Commercial shell-fishing throughout public waters is also big business, but this article is about recreational shell-fishing – exercise, fun, outdoors, COVID-safe, and you get dinner. So, you want some clams, do you? Here is what you’ll need to do:

1. Get a license. Like a fishing license, recreational shell-fishers need a license. A shellfish license will allow you to take limited quantities of clams, oysters, scallops, etc., but a separate license is needed if you want lobster. While lobster licenses are issued by the state, recreational shellfish licenses are town-specific, so you can only take clams from the town in which you bought the license. You can buy a license for more than one town, but once you’ve found your “honey hole,” why bother? Licenses typically last for one year. The money you pay for your license supports the local Department of Natural Resources (DNR). As I said above, nature cannot keep up with the demand for shellfish. Everybody wants to visit Cape Cod, and everybody wants to eat clams (and lobsters) when they are there. The locals want fresh seafood too! The DNR collects and cultivates clam spawn and grows the clams until they are of legal size. This takes place in local hatcheries and nurseries. Every few weeks throughout the summer, when the clams are large enough, they are taken to select locations by small boat and are then thrown overboard, to supplement what nature can provide and give clam diggers a continuous supply. The DNR publishes maps of legal areas to clam, some of which are only open part of the year, but they don’t tell you when they seed. However, if you time it right, you can watch where the boat goes and see exactly where they are dumped. Grin.

2. Get the right equipment. You will need a strong clamming rake, a clamming basket, and a measuring tool. For hard shell clamming you will want a long-handled rake; for soft shell clamming you will want a different kind of rake. The size of your metal clamming basket is 1 peck, which is about 10 quarts. Your shellfish license will allow you to take 1 level peck each week. A week is defined as starting on Sunday and ending on Saturday. You are permitted to clam on only Sundays, Wednesdays, and Saturdays. You can split your take throughout those 3 days, but the total catch cannot exceed 1 level peck in a week. You will want some kind of flotation for your basket so it doesn’t sink, and a leash so that it doesn’t float away. You can buy a flotation ring or simply attach pool noodles with wire ties. A rope of any kind tied to the handle of your basket and around your waist will keep your catch close at hand. You will need a measuring tool that is essentially a small rectangular piece of sheet metal with a rectangular hole. The width of the rectangle is 1 inch – the minimum thickness of a legal clam. When you measure your clam, if it fits through the hole, then it’s too small and you should throw it back. Most people like the littlenecks the best as they are the sweetest, but if you keep one that is too small and get caught there is a hefty fine per clam. You won’t need a flashlight or a headlamp as clamming hours are from ½ hour before sunrise to sunset. The best time to go is low tide, so that it is easier to dig and you can walk out further from shore.

3. So, you’ve got your basket full of clams, now what? Clean them – inside and out. Inside? Yes, inside. It will take a few hours, but clean them. Hours? Yes, hours. Don’t worry, it’s not as bad as you think. Clams are filter feeders meaning that they siphon in water, extract nutrients and then expel the water. Sometimes sand and grit come in with the water and since you probably don’t want a sandy meal for yourself, you’ll want to get rid of that. Actually, you’ll want the clam to prepare itself to be eaten. Sounds a little funny, but that’s the way it is. All you have to do is supply clean water. Fill a bucket with seawater, put in your clams, and over the course of a few hours they will clean themselves, siphoning in the clean seawater and purging the junk. But, as the clams like to live in the sediment, you will have to scrub the outside of the shells. They can’t do that by themselves. Ha.

Once your clams are clean you can open them with a knife and have them on the half shell or you can cook them any way you please. I like to steam them open and have them over pasta with olive oil and garlic. Guess what’s for dinner tonight? Spaghetti alle vongole (Italian word for clams) and I will be happy as a clam. Buon appetito!!

![]() Cardinal in the snow

Cardinal in the snow

Stan Chamberlain, BEACON Contributing Editor

The snow is deep in Barrington (Rhode Island, USA), but not too deep for the birds to come visiting.

Dr. James V. Candy is the Chief Scientist for Engineering and former Director of the Center for Advanced Signal & Image Sciences at the University of California, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Dr. Candy received a commission in the USAF in 1967 and was a Systems Engineer/Test Director from 1967 to 1971. He has been a Researcher at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory since 1976 holding various positions including that of Project Engineer for Signal Processing and Thrust Area Leader for Signal and Control Engineering. Educationally, he received his B.S.E.E. degree from the University of Cincinnati and his M.S.E. and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical Engineering from the University of Florida, Gainesville. He is a registered Control System Engineer in the state of California. He has been an Adjunct Professor at San Francisco State University, University of Santa Clara, and UC Berkeley, Extension teaching graduate courses in signal and image processing. He is an Adjunct Full-Professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Dr. Candy is a Fellow of the IEEE and a Fellow of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) and elected as a Life Member (Fellow) at the University of Cambridge (Clare Hall College). He is a member of Eta Kappa Nu and Phi Kappa Phi honorary societies. He was elected as a Distinguished Alumnus by the University of Cincinnati. Dr. Candy received the IEEE Distinguished Technical Achievement Award for the “development of model-based signal processing in ocean acoustics.” Dr. Candy was selected as a IEEE Distinguished Lecturer for oceanic signal processing as well as presenting an IEEE tutorial on advanced signal processing available through their video website courses. He was nominated for the prestigious Edward Teller Fellowship at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Dr. Candy was awarded the Interdisciplinary Helmholtz-Rayleigh Silver Medal in Signal Processing/Underwater Acoustics by the Acoustical Society of America for his technical contributions. He has published over 225 journal articles, book chapters, and technical reports as well as written three texts in signal processing, “Signal Processing: the Model-Based Approach,” (McGraw-Hill, 1986), “Signal Processing: the Modern Approach,” (McGraw-Hill, 1988), “Model-Based Signal Processing,” (Wiley/IEEE Press, 2006) and “Bayesian Signal Processing: Classical, Modern and Particle Filtering” (Wiley/IEEE Press, 2009). He was the General Chairman of the inaugural 2006 IEEE Nonlinear Statistical Signal Processing Workshop held at the Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge. He has presented a variety of short courses and tutorials sponsored by the IEEE and ASA in Applied Signal Processing, Spectral Estimation, Advanced Digital Signal Processing, Applied Model-Based Signal Processing, Applied Acoustical Signal Processing, Model-Based Ocean Acoustic Signal Processing and Bayesian Signal Processing for IEEE Oceanic Engineering Society/ASA. He has also presented short courses in Applied Model-Based Signal Processing for the SPIE Optical Society. He is currently the IEEE Chair of the Technical Committee on “Sonar Signal and Image Processing” and was the Chair of the ASA Technical Committee on “Signal Processing in Acoustics” as well as being an Associate Editor for Signal Processing of ASA (on-line JASAXL). He was recently nominated for the Vice Presidency of the ASA and elected as a member of the Administrative Committee of IEEE OES. His research interests include Bayesian estimation, identification, spatial estimation, signal and image processing, array signal processing, nonlinear signal processing, tomography, sonar/radar processing and biomedical applications.

Dr. James V. Candy is the Chief Scientist for Engineering and former Director of the Center for Advanced Signal & Image Sciences at the University of California, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Dr. Candy received a commission in the USAF in 1967 and was a Systems Engineer/Test Director from 1967 to 1971. He has been a Researcher at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory since 1976 holding various positions including that of Project Engineer for Signal Processing and Thrust Area Leader for Signal and Control Engineering. Educationally, he received his B.S.E.E. degree from the University of Cincinnati and his M.S.E. and Ph.D. degrees in Electrical Engineering from the University of Florida, Gainesville. He is a registered Control System Engineer in the state of California. He has been an Adjunct Professor at San Francisco State University, University of Santa Clara, and UC Berkeley, Extension teaching graduate courses in signal and image processing. He is an Adjunct Full-Professor at the University of California, Santa Barbara. Dr. Candy is a Fellow of the IEEE and a Fellow of the Acoustical Society of America (ASA) and elected as a Life Member (Fellow) at the University of Cambridge (Clare Hall College). He is a member of Eta Kappa Nu and Phi Kappa Phi honorary societies. He was elected as a Distinguished Alumnus by the University of Cincinnati. Dr. Candy received the IEEE Distinguished Technical Achievement Award for the “development of model-based signal processing in ocean acoustics.” Dr. Candy was selected as a IEEE Distinguished Lecturer for oceanic signal processing as well as presenting an IEEE tutorial on advanced signal processing available through their video website courses. He was nominated for the prestigious Edward Teller Fellowship at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Dr. Candy was awarded the Interdisciplinary Helmholtz-Rayleigh Silver Medal in Signal Processing/Underwater Acoustics by the Acoustical Society of America for his technical contributions. He has published over 225 journal articles, book chapters, and technical reports as well as written three texts in signal processing, “Signal Processing: the Model-Based Approach,” (McGraw-Hill, 1986), “Signal Processing: the Modern Approach,” (McGraw-Hill, 1988), “Model-Based Signal Processing,” (Wiley/IEEE Press, 2006) and “Bayesian Signal Processing: Classical, Modern and Particle Filtering” (Wiley/IEEE Press, 2009). He was the General Chairman of the inaugural 2006 IEEE Nonlinear Statistical Signal Processing Workshop held at the Corpus Christi College, University of Cambridge. He has presented a variety of short courses and tutorials sponsored by the IEEE and ASA in Applied Signal Processing, Spectral Estimation, Advanced Digital Signal Processing, Applied Model-Based Signal Processing, Applied Acoustical Signal Processing, Model-Based Ocean Acoustic Signal Processing and Bayesian Signal Processing for IEEE Oceanic Engineering Society/ASA. He has also presented short courses in Applied Model-Based Signal Processing for the SPIE Optical Society. He is currently the IEEE Chair of the Technical Committee on “Sonar Signal and Image Processing” and was the Chair of the ASA Technical Committee on “Signal Processing in Acoustics” as well as being an Associate Editor for Signal Processing of ASA (on-line JASAXL). He was recently nominated for the Vice Presidency of the ASA and elected as a member of the Administrative Committee of IEEE OES. His research interests include Bayesian estimation, identification, spatial estimation, signal and image processing, array signal processing, nonlinear signal processing, tomography, sonar/radar processing and biomedical applications. Kenneth Foote is a Senior Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. He received a B.S. in Electrical Engineering from The George Washington University in 1968, and a Ph.D. in Physics from Brown University in 1973. He was an engineer at Raytheon Company, 1968-1974; postdoctoral scholar at Loughborough University of Technology, 1974-1975; research fellow and substitute lecturer at the University of Bergen, 1975-1981. He began working at the Institute of Marine Research, Bergen, in 1979; joined the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in 1999. His general area of expertise is in underwater sound scattering, with applications to the quantification of fish, other aquatic organisms, and physical scatterers in the water column and on the seafloor. In developing and transitioning acoustic methods and instruments to operations at sea, he has worked from 77°N to 55°S.

Kenneth Foote is a Senior Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. He received a B.S. in Electrical Engineering from The George Washington University in 1968, and a Ph.D. in Physics from Brown University in 1973. He was an engineer at Raytheon Company, 1968-1974; postdoctoral scholar at Loughborough University of Technology, 1974-1975; research fellow and substitute lecturer at the University of Bergen, 1975-1981. He began working at the Institute of Marine Research, Bergen, in 1979; joined the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in 1999. His general area of expertise is in underwater sound scattering, with applications to the quantification of fish, other aquatic organisms, and physical scatterers in the water column and on the seafloor. In developing and transitioning acoustic methods and instruments to operations at sea, he has worked from 77°N to 55°S. René Garello, professor at Télécom Bretagne, Fellow IEEE, co-leader of the TOMS (Traitements, Observations et Méthodes Statistiques) research team, in Pôle CID of the UMR CNRS 3192 Lab-STICC.

René Garello, professor at Télécom Bretagne, Fellow IEEE, co-leader of the TOMS (Traitements, Observations et Méthodes Statistiques) research team, in Pôle CID of the UMR CNRS 3192 Lab-STICC. Professor Mal Heron is Adjunct Professor in the Marine Geophysical Laboratory at James Cook University in Townsville, Australia, and is CEO of Portmap Remote Ocean Sensing Pty Ltd. His PhD work in Auckland, New Zealand, was on radio-wave probing of the ionosphere, and that is reflected in his early ionospheric papers. He changed research fields to the scattering of HF radio waves from the ocean surface during the 1980s. Through the 1990s his research has broadened into oceanographic phenomena which can be studied by remote sensing, including HF radar and salinity mapping from airborne microwave radiometers . Throughout, there have been one-off papers where he has been involved in solving a problem in a cognate area like medical physics, and paleobiogeography. Occasionally, he has diverted into side-tracks like a burst of papers on the effect of bushfires on radio communications. His present project of the Australian Coastal Ocean Radar Network (ACORN) is about the development of new processing methods and applications of HF radar data to address oceanography problems. He is currently promoting the use of high resolution VHF ocean radars, based on the PortMap high resolution radar.

Professor Mal Heron is Adjunct Professor in the Marine Geophysical Laboratory at James Cook University in Townsville, Australia, and is CEO of Portmap Remote Ocean Sensing Pty Ltd. His PhD work in Auckland, New Zealand, was on radio-wave probing of the ionosphere, and that is reflected in his early ionospheric papers. He changed research fields to the scattering of HF radio waves from the ocean surface during the 1980s. Through the 1990s his research has broadened into oceanographic phenomena which can be studied by remote sensing, including HF radar and salinity mapping from airborne microwave radiometers . Throughout, there have been one-off papers where he has been involved in solving a problem in a cognate area like medical physics, and paleobiogeography. Occasionally, he has diverted into side-tracks like a burst of papers on the effect of bushfires on radio communications. His present project of the Australian Coastal Ocean Radar Network (ACORN) is about the development of new processing methods and applications of HF radar data to address oceanography problems. He is currently promoting the use of high resolution VHF ocean radars, based on the PortMap high resolution radar. Hanu Singh graduated B.S. ECE and Computer Science (1989) from George Mason University and Ph.D. (1995) from MIT/Woods Hole.He led the development and commercialization of the Seabed AUV, nine of which are in operation at other universities and government laboratories around the world. He was technical lead for development and operations for Polar AUVs (Jaguar and Puma) and towed vehicles(Camper and Seasled), and the development and commercialization of the Jetyak ASVs, 18 of which are currently in use. He was involved in the development of UAS for polar and oceanographic applications, and high resolution multi-sensor acoustic and optical mapping with underwater vehicles on over 55 oceanographic cruises in support of physical oceanography, marine archaeology, biology, fisheries, coral reef studies, geology and geophysics and sea-ice studies. He is an accomplished Research Student advisor and has made strong collaborations across the US (including at MIT, SIO, Stanford, Columbia LDEO) and internationally including in the UK, Australia, Canada, Korea, Taiwan, China, Japan, India, Sweden and Norway. Hanu Singh is currently Chair of the IEEE Ocean Engineering Technology Committee on Autonomous Marine Systems with responsibilities that include organizing the biennial IEEE AUV Conference, 2008 onwards. Associate Editor, IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering, 2007-2011. Associate editor, Journal of Field Robotics 2012 onwards.

Hanu Singh graduated B.S. ECE and Computer Science (1989) from George Mason University and Ph.D. (1995) from MIT/Woods Hole.He led the development and commercialization of the Seabed AUV, nine of which are in operation at other universities and government laboratories around the world. He was technical lead for development and operations for Polar AUVs (Jaguar and Puma) and towed vehicles(Camper and Seasled), and the development and commercialization of the Jetyak ASVs, 18 of which are currently in use. He was involved in the development of UAS for polar and oceanographic applications, and high resolution multi-sensor acoustic and optical mapping with underwater vehicles on over 55 oceanographic cruises in support of physical oceanography, marine archaeology, biology, fisheries, coral reef studies, geology and geophysics and sea-ice studies. He is an accomplished Research Student advisor and has made strong collaborations across the US (including at MIT, SIO, Stanford, Columbia LDEO) and internationally including in the UK, Australia, Canada, Korea, Taiwan, China, Japan, India, Sweden and Norway. Hanu Singh is currently Chair of the IEEE Ocean Engineering Technology Committee on Autonomous Marine Systems with responsibilities that include organizing the biennial IEEE AUV Conference, 2008 onwards. Associate Editor, IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering, 2007-2011. Associate editor, Journal of Field Robotics 2012 onwards. Milica Stojanovic graduated from the University of Belgrade, Serbia, in 1988, and received the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from Northeastern University in Boston, in 1991 and 1993. She was a Principal Scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and in 2008 joined Northeastern University, where she is currently a Professor of electrical and computer engineering. She is also a Guest Investigator at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Milica’s research interests include digital communications theory, statistical signal processing and wireless networks, and their applications to underwater acoustic systems. She has made pioneering contributions to underwater acoustic communications, and her work has been widely cited. She is a Fellow of the IEEE, and serves as an Associate Editor for its Journal of Oceanic Engineering (and in the past for Transactions on Signal Processing and Transactions on Vehicular Technology). She also serves on the Advisory Board of the IEEE Communication Letters, and chairs the IEEE Ocean Engineering Society’s Technical Committee for Underwater Communication, Navigation and Positioning. Milica is the recipient of the 2015 IEEE/OES Distinguished Technical Achievement Award.

Milica Stojanovic graduated from the University of Belgrade, Serbia, in 1988, and received the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from Northeastern University in Boston, in 1991 and 1993. She was a Principal Scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and in 2008 joined Northeastern University, where she is currently a Professor of electrical and computer engineering. She is also a Guest Investigator at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Milica’s research interests include digital communications theory, statistical signal processing and wireless networks, and their applications to underwater acoustic systems. She has made pioneering contributions to underwater acoustic communications, and her work has been widely cited. She is a Fellow of the IEEE, and serves as an Associate Editor for its Journal of Oceanic Engineering (and in the past for Transactions on Signal Processing and Transactions on Vehicular Technology). She also serves on the Advisory Board of the IEEE Communication Letters, and chairs the IEEE Ocean Engineering Society’s Technical Committee for Underwater Communication, Navigation and Positioning. Milica is the recipient of the 2015 IEEE/OES Distinguished Technical Achievement Award. Dr. Paul C. Hines was born and raised in Glace Bay, Cape Breton. From 1977-1981 he attended Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, graduating with a B.Sc. (Hon) in Engineering-Physics.

Dr. Paul C. Hines was born and raised in Glace Bay, Cape Breton. From 1977-1981 he attended Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, graduating with a B.Sc. (Hon) in Engineering-Physics.